In the fall, an LIS foundations course of mine delved deeply into the discussion of librarian stereotypes. The books and articles we read gave us several prototypical examples. In chronological order (according to character described, not era written about in) here are the biggies that stood out:

- “A Room of One’s Own” by Virginia Woolf, first published in 1929, portrayed the librarian as an intimidating male authority figure protecting knowledge from the lesser classes and genders.

- The Dismissal of Miss Ruth Brown by Louise S. Robbins, published in 2001, profiled a real-life late-1940s librarian who was a stubborn but progressively minded middle-aged woman–barely a mother and never a wife–performing one of the few jobs allowed for females of that era. The cover of the book is a picture of her wearing glasses, hair pulled back (potentially in a librarian bun?).

- “How My Hometown Library Failed Me” by Anne Nelson, originally published February 1, 1978, didn’t so much discuss the librarians directly, but from her descriptions of the library’s collection, the reader gets the picture the librarians there were nosey and over-protective censors, like over-bearing mothers with too much time on their hands.

- The 2010 Library Journal Movers & Shakers seemed to be an attempt at re-branding the image of the librarian, from a grumpy old shushing lady to one of an energetic, hip, potentially tattooed professional who could be of any race or gender. This is not just “pink collar” work for whites! We wear our hair all sorts of ways!

I have all these cultural images of the “librarian” in my head as I get into the thick of reading H. P. Lovecraft’s “The Dunwich Horror.” To my delight, the hero-protagonist of that story soon proved to be the head librarian at Miskatonic University in Arkham. He could be compared to the male academician of Woolf’s story–the two stories are both discussing the same era and were conceived and published then. But while the Woolf character was described as an unpermissive gatekeeper (not the positive kind), Lovecraft’s librarian, Dr. Henry Armitage, saved not only the townspeople of Dunwich but potentially the entire world. How’s that for a librarian’s work? 🙂

Being an MLIS student really brought joy to reading this tale. I can get a bit bogged down with all the negative associations with the term “librarian” and think the re-branding efforts can seem really forced sometimes. (See “Info Pro: Adopting the Tools from the World of Business Consulting,” from the January 2011 issue of American Libraries. If I were to turn in an article like that to my first journalism writing class, I would have gotten an F for using too much jargon. Red-inked edits would be everywhere.)

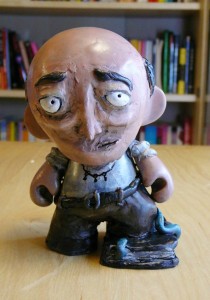

Henry Armitage, A.M. Miskatonic, Ph.D., Princeton, Litt.D. Johns Hopkins. Sculpture imagined and executed by Ben Stirling, from attemptedartistry.blogspot.com.

Our Lovecraftian librarian here is full of knowledge, courage, and curiosity. That is something positive that I could really identify with. Armitage is an obsessive reader (of a diary written by an otherworldly creature), and although he’s an authority, he uses his librarian power to prevent this barely-human Wilbur Wheatley from checking out the ancient tome that would allow him to raise up inconceivably monstrous ancient ones.

Armitage can decipher codes, too, and throughout his scenes he is continually stricken with feelings of grave responsibility. He is weakened by several days of not eating while obsessively reading the maddening text, but hey, he is 73 years old, after all.

This story gives me new hope for that term. From now on when I think of “librarians,” I will not settle for images of the tattooed and pierced. Rather, I will look at librarians as if each of them had the courage to investigate and prevent the “hellish advance in the black dominion of [an] ancient and once passive nightmare.”

Don’t have to let down the bun for that.

Armitage plays gatekeeper, but he gives Wilbur massive benefit of the doubt. Armitage knew something of Wilbur’s insane background (a backwoods child rapidly maturing far beyond human capability), and despite that and his terrifying appearance, he helped Wilbur find the rare book he wanted, and translated sections for him. That’s pretty generous.

PS: I don’t know that I’d bother with the two film editions of The Dunwich Horror. But the radio play by the HP Lovecraft Historical Society of “The Dunwich Horror” is excellent, especially many of the Armitage scenes.

We need more librarians like Armitage! Imagine someone breaks into the local university library to steal a tome from Special Collections. Would our modern library director form an interdisciplinary team of adventurers consisting of professors in languages and medicine in order to investigate the crimes surrounding the book’s disappearance? NO.

Jeb, I’m so sorry I’m just now seeing your comment. I must have to adjust my settings so that these things (and not all the WordPress spam) come through my email.

You’re right that Armitage provides assistance to Wilbur–that’s the librarian’s role, to facilitate information retrieval. What I love is the tension between both sides of the responsibility coin. These types of information/artifact curators are there to protect but serve.

I think Lovecraft used that (wittingly or un-) to the story’s advantage. If Armitage biased his protective instincts over his service ones, the plot could have stopped dead in its tracks. But the delay there–the one caused by the professional doing his duty thoroughly, spurred by both responsibility and curiosity (or the demand for knowledge)–made it so that the unraveling of events in Dunwich quickened pace. I really loved the tension created there.

Also, thanks for the tip about the Society’s radio play. I just watched the ’70s film last night, and I’m glad I did. Got some good schlock in, but could have done without the slasher parts. The story’s of course better–Wilbur needs to be torn apart by dogs. The animation and invisible horror made it worth it, tho, imho.